By Bob

By Bob

Sam Jethroe and Me

This article was written in 1997, when Sam Jethroe finally won a pension from Major League Baseball. Sam died in 2001 at 83.

I was tickled to see Sam Jethroe's name in the news last week. The last time before that might have been 20 years ago, maybe even 30. Jethroe is an old (he must be near 80 now) black baseball player who finally, after considerable legal wrangling, wrestled a pension out of Major League Baseball. He is not famous, really; his major league career spanned just a few years in the early 1950s.

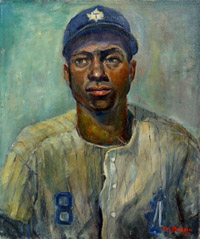

I suppose I think of Sam Jethroe more often than just about anyone who doesn't know him personally. That's because I have on my wall a remarkable oil painting of Sam. It was painted by Marcia Bossin, my mother, in 1957. In the painting, Jethroe, who would have then been in his 30s, is a handsome, sad-eyed man in a baseball cap who does not quite look at you. His expression is as ineffable as the Mona Lisa's.

In those days, the mid-50s, Jethroe played for the Toronto Maple Leafs Baseball Club, a "triple A" team, one rung below the majors. His big-league career had been notable but short. He was one of the first blacks to follow Jackie Robinson over the colour bar. In 1950, he was National League rookie-of-the-year. But after just over 3 seasons, age caught up with him, and he was demoted to Toronto.

Jethroe, like many of the Leafs, lived in the Barclay Hotel at Front and York, a few blocks from Toronto's old lakeside stadium. My father's office - he booked the acts into the hotel's night-club - was also in the Barclay. I would often see the tall, athletic young ballplayers lounging around the lobby and check them against their photos in the Barclay's smokeshop.

Jethroe was my favourite. This was because, at the first ball game I ever saw (I would have been 7 or 8), he stole a base. That was all it took back then, but once I gave my heart, I was faithful. I followed the waning years of Sam's career devotedly and even negotiated a deal where-by I stayed up to hear his first at-bat on the old fictionalized game broadcasts. (Against a background loop of crowd noise, the announcer would make up the play-by-play from the bare-bones coded version on the news wire.) Jethroe and I grew older together, me staying up ever later while he slipped farther down the batting order. At Sunday double-headers, I watched as he was shifted from centrefield to left field, then to right, then to "utility" outfielder, to pinch-runner. All the while, above my bed was Sam Jethroe's photo from the Barclay smokeshop, messily autographed. I still have it. I have always wondered whether his fountain pen had trouble negotiating the glossy surface of the picture or whether he found writing more difficult than hitting a curve.

My mother painted the portrait from that photograph. It was bought by my uncle, the writer and columnist, Hye Bossin. I complained long enough that he willed it to me. When he died in 1964, the painting became mine. It has moved with me ever since, flat to flat, Toronto to Vancouver to Gabriola Island, pretty much the only possession I have had all that time.

It was while looking at that painting, in 1971, that I wrote "Daddy Was a Ballplayer", a song some long-in-the-tooth readers may remember. The daddy in the song is really Sam Jethroe, as I imagined his son saw him. A decade later, again looking at the painting, I wrote "The Secret of Life According to Satchel Paige" which I am flattered to have heard described as one of the best baseball songs - a small pond, admittedly. Beneath my retelling of Paige's tall tales and legendary deeds is my boyhood love for Sam Jethroe.

So it was great to hear he is still alive and kicking. I am glad he finally won his pension, glad the baseball owners at last acknowledged the injustice to Sam and the other black players in the same boat. Late though it has come, the decision attempts to redress an old wrong - the one Satchel Paige summed up so succinctly when he said, "If they all think we was so good, how come they never give us no justice?"